Viewpoints

Happy New Year from all of us on Mill Street. What an eventful year it has been - one shaped by shifting data, shifting narratives, and no shortage of surprises.

As we turn the page, we’ve been thinking about how much professional sports have changed in recent years, largely because of analytics. In the NFL, fourth-down attempts are no longer acts of desperation but of probability. In basketball, the three-point revolution has reshaped offenses from the ground up. And in hockey, teams are pulling their goalies earlier than ever in pursuit of the extra attacker. And as for Major League Baseball, the sport analytics practically rebuilt from the inside out, it scarcely needs mentioning.

Each sport, in its own way, has been transformed by the cold math of expected value. And yet, despite the data, teams often stop short of going as far as the analytics suggest they should. Hockey is the clearest example: even with goalies being pulled earlier than ever, the numbers show they should be pulled earlier still. Coaches know this, and the probabilities are not in dispute. But they rarely take the leap..

Why? Partly because of perception. An empty net looks like panic, even when the strategy improves the odds of winning.

That tension, the gap between what we know and what we are willing to act on, is not unique to sports. It is alive and well in financial markets, too. Investors know valuations are stretched, particularly with the Magnificent Seven occupying rarefied air, and that concentration risk has become its own form of fragility. And yet the buying continues, not always out of conviction, but because the alternative of holding cash, bonds, or diversifiers while the index surges, looks wrong.

A Quick Case Study on Professional Hockey

We’re all familiar with the 1980 “Miracle on Ice,” one of America’s greatest sporting triumphs - a young U.S. team stunning the seemingly unbeatable Soviets on the Olympic stage. It’s a story most of us know well, and it sets up an often-overlooked detail that matters for where we’re going.

In that semifinal game, Team USA took a 4-3 lead with ten minutes left in the third period. What followed was a relentless Soviet assault, turned away again and again by the Americans, who even managed a few dangerous chances the other way. But as the clock drained away, something curious happened: Viktor Tikhonov, the legendary Soviet coach, never pulled his goaltender to bring on a sixth attacker.

After the fact, Soviet defenseman Sergei Starikov offered the simplest explanation imaginable: “We never did six-on-five,” he said, not even in practice, because “Tikhonov just didn’t believe in it.”

Pulling the goalie, of course, is one of hockey’s great dramatic gambits, traditionally traced back to 1931 when Boston Bruins coach Art Ross yanked Tiny Thompson in the final minute of a playoff game against Montreal. It didn’t work, Boston lost 1–0, but a strategic tradition was born.

Photo Credit: Heinz Kluetmeier 1942 –2025

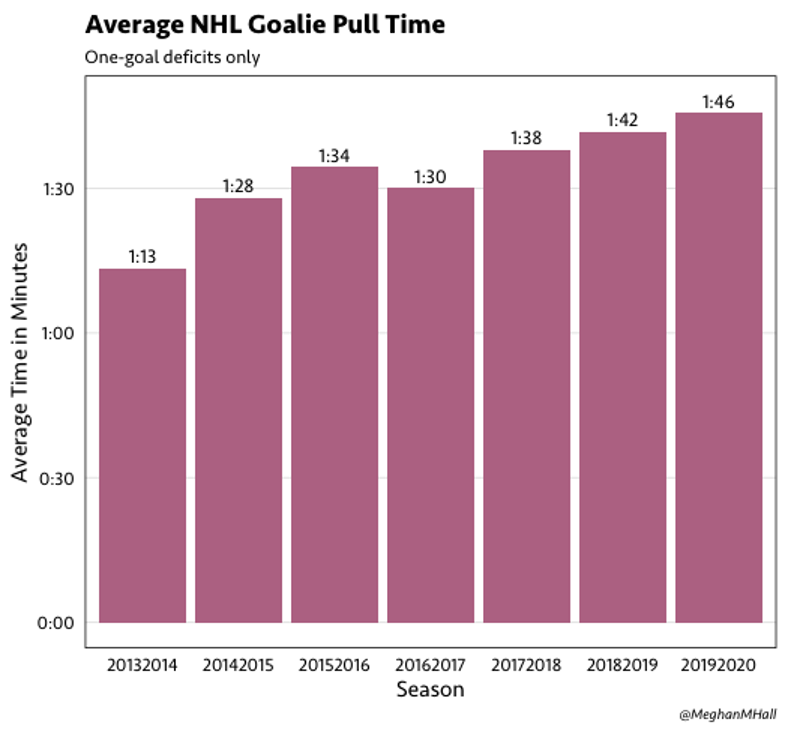

This brings us to the modern day, where over the last decade teams have begun pulling their goalie earlier and earlier. Yet even with that shift, 98% of pulls still occur with under two minutes remaining. As shown in Chart 1, the average pull time has inched earlier between 2013 and 2020 - but not nearly as much as the analytics suggest it should.

CHART 1, SOURCE: HOCKEY-GRAPHS.COM

What the Math Says

While the trend of pulling goalies earlier is headed in the right direction, the math says it is still nowhere near early enough. Numerous studies have examined this question, and the consensus is striking: for a team down by one goal in the third period, the optimal time to pull the goalie - maximizing expected points added - is roughly four minutes and twenty seconds remaining (and some studies push that number closer to six minutes). That is a far cry from today’s norm of waiting until under two minutes.

For what it’s worth, the math gets even more counterintuitive when a team is down by two goals: the optimal pull time jumps to nearly thirteen minutes remaining. That may sound extreme, but so did many strategies that are now widely accepted across professional sports - not least of which were considered radical barely a decade ago.

So why don’t coaches follow the math? The answer is rarely strategic and almost always psychological. Pulling the goalie with six, or thirteen, minutes left may maximize expected outcomes, but it also maximizes visibility. An empty net is a billboard announcing risk-taking, and if it backfires, everyone sees it. Coaches know that conceding an empty-net goal with half a period to play will be met with second-guessing, headlines, and talk-radio autopsies. Keeping the goalie in, even when the probabilities argue otherwise, offers the comfort of plausible deniability: we played it straight; the puck simply didn’t bounce our way.

In other words, the data encourages boldness, but the optics reward caution.

The Empty Net Psychology In Investing

This tension between what the numbers suggest and what human beings are willing to act on is not confined to hockey. Investors face the same dilemma. Markets routinely present situations where the data points one way and perception pulls in another. We know when valuations are stretched. We know when concentration risk is rising. We know when a handful of megacap stocks are carrying the market on their backs. And yet, just like a coach staring at an empty net, many investors hesitate to act on that knowledge - not because the probabilities are unclear, but because the optics of not playing along can feel even worse.

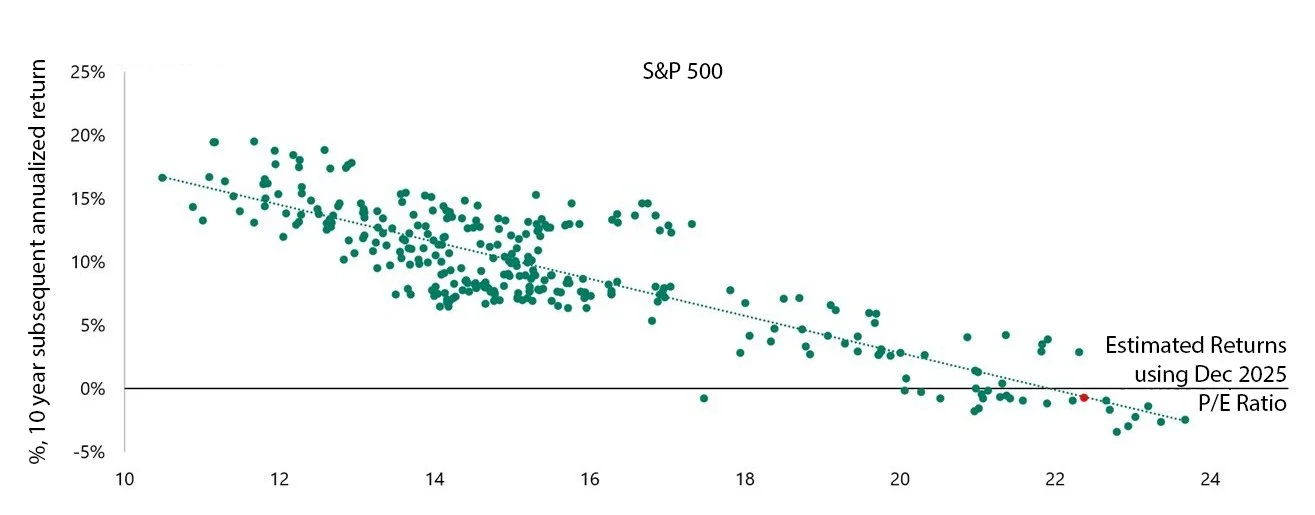

Just as coaches resist pulling the goalie early, even when the math argues for it, investors often resist stepping back from an expensive market, even when the data is unambiguous. At today’s valuations, the numbers paint a sobering picture. With the S&P 500 trading around 23× forward earnings, the historical relationship between starting valuations and future returns suggests that expected 10-year forward returns are, in theory, close to zero (see Chart 2). That doesn’t mean the market must fall, only that the runway for compounding narrows dramatically when you start from this altitude.

CHART 2, SOURCE: APOLLO

The concentration story is just as striking. The U.S. equity market has become so top-heavy that Nvidia alone now represents nearly 8% of the entire S&P 500, a weight normally reserved for broad sectors, not single companies. The Magnificent Seven, for all their innovation and earnings power, have reached levels of market dominance that are difficult to reconcile with traditional diversification principles. And yet, inflows continue, momentum builds on itself, and the fear of “being left behind” often overrides sober analysis.

This is the investor’s version of staring at the empty net.

None of this is to say that technology or the Magnificent Seven are destined to collapse. But when a narrow group of companies commands this much market value, growth expectation, and investor mindshare, it begins to take on the visual profile of a bubble - regardless of how strong the underlying businesses may be. What matters for investors is not whether these companies remain innovative, but whether the prices already assume a future that leaves little room for surprise.

Fortunately, the market is far larger than its most crowded corners. Beyond the megacaps, there are entire segments, both in the U.S. and abroad, that remain unloved yet highly resilient: businesses with stable cash flows, durable competitive positions, and valuations that still leave ample room for compounding. Many of these areas have quietly strengthened while the spotlight stayed fixed on a handful of tech giants. Dividend-oriented companies, quality cyclicals, and select international markets offer characteristics that, in our opinion, can help investors participate in equity growth without relying on the continued perfection of a very small group of firms.

In Conclusion

In the end, the lesson from sports is the same lesson from markets: data can illuminate the path, but it cannot force us to take it. Coaches know the probabilities but often stick with convention because the alternatives “look wrong.” Investors face the same fork in the road. When the familiar feels safe, no matter what the math suggests, it becomes tempting to leave the goalie in net and hope for a lucky bounce.

But successful investing, like successful coaching, requires a willingness to step back from the noise and position oneself where the probabilities are strongest. At SG&Co., our focus remains on building portfolios that attempt to balance resilience with opportunity: emphasizing durable cash flows for enhanced dividends, reasonable valuations, and global exposures that can compound quietly while the spotlight chases whatever is fashionable in the moment.

As we begin a new year on Mill Street, our aim is the same as always: to navigate uncertainty with discipline, avoid the seduction of crowded trades, and seek out areas of the market where patience and prudence are still rewarded. Markets will continue to surprise us, narratives will continue to shift, and analytics will continue to challenge long-held assumptions. But through it all, the fundamentals of long-term investing remain remarkably constant.

Here’s to a disciplined and well-grounded year ahead.

Michael P. Moeller, CIMA®

Portfolio Manager & Director of Research